On Proyecto Desaparecidos' 'Muro de la Memoria'

The Muro invokes the unresolved nature of disappearance, reminding us of the special anguish this crime inflicts. It is also an invitation to action.

This text originally published: 15 October 2006

This reflection focuses on an online gallery called “Muro de la Memoria (Wall of Memory)” of victims of the Argentine military dictatorship of 1976 to 1983. The gallery is the creation of a loose grouping of activists and organizations known as Proyecto Desaparecidos (Project Disappeared). Proyecto Desaparecidos describes its mission thusly:

Project Disappeared is a joint project of several human rights organizations and activists with the purpose of recovering and maintaining memory, understanding what happened in Argentina during the “dirty war” and fighting against impunity. We invite you to visit it, to contribute, to join our efforts—and above all, to remember.1

“Muro de la Memoria” is hosted on Proyecto Desparecidos’ website, Desaparecidos.org (www.desaparecidos.org). A brief introduction to the gallery is available at www.desaparecidos.org/arg/victimas/ and the actual gallery is at www.desaparecidos.org/arg/victimas/muro2.html (Note that the gallery takes several minutes to load).

Before exploring my reactions to the exhibit, a bit of historical context for the gallery is in order. On 24 March 1976, Argentina experienced a military coup d’état. The junta that took power from the civilian government was the latest in Argentina’s long history of military regimes, but a distinguishing characteristic of the 1976 coup was that it occurred amid the Cold War and followed a series of similar military coups in neighboring states: Bolivia (1971), Brazil (1964), Chile (1973), and Uruguay (1973), with Paraguay under an elected but highly authoritarian ruler since 1954. The Argentine junta, ostensibly in order to suppress the insurgent Montoneros, implemented a campaign of repression that included the systematic use of concentration camps and state-sanctioned disappearances, torture, and murder of civilians. The junta also coordinated with the other regional dictatorships and the United States to monitor and detain or eliminate political opponents who attempted to flee to neighboring states. Victims of the dictatorship were frequently abducted from their homes and workplaces, sometimes in daylight, and then inserted into the regime’s network of clandestine detention centers, whence all manner of humiliation, torture, and worse ensued. By the time the junta collapsed in 1983, as many as 30,000 people had been disappeared in Argentina alone.

Since the collapse of the regime, while individual perpetrators may have knowledge of the fates of particular victims, for friends and family members of the victims the agony of disappearance derives in large part from the open-ended nature of the crime. In essence, until paper trails, forensic evidence, or perpetrator admissions say otherwise, a disappearance is an unresolved, ongoing crime. It is precisely the open status of these cases that has contributed to the dynamism of the memory movement in Argentina: because the crimes are not finished and the cases are not closed, the act of remembering the disappeared simultaneously invokes the past and the present while also enabling efforts to end the perpetrators’ impunity in the country’s courts. It is this linkage of active memory with active legal campaigns that has made the Argentine and other South American memory movements models for victims of state terror around the world.

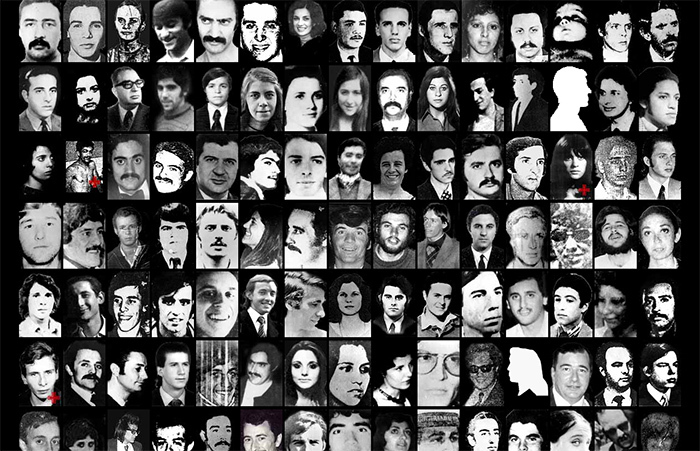

“Muro de la Memoria” is an example of this active memory at work. In simple rows and columns on a black field, “Muro” displays black and white portraits of over 1,300 disappeared from the 1976-1983 dictatorship. Aside from a title at the very top of the gallery, there are no texts or captions on the page—just photo after photo of the victims’ faces staring back at the viewer. On one ironical level, the effect of regarding this orderly arrangement is not unlike the experience of visiting military cemeteries, with their evenly spaced headstones that invariably speak to the scale of the human losses symbolized by the markers.

But the photographs in the “Muro” are far more personal than the uniform headstones of a military burial ground, for the victims’ faces express an entire range of emotions and suggest a slew of lives and biographies that were cut short. There are old people, middle-aged people, many young people, and even some infants. Some of the images are smiling portraits—photos drawn from happy moments at parties or on vacations. Other portraits have the sterile, institutional quality of official identification shots or school yearbooks. Many of the portraits are highly deteriorated, while others are clear, almost as if new. Likewise, some of the victims follow the fashions and styles of their day, while others appear strangely contemporaneous to our current age.

One can stare at the “Muro” at length, studying the faces of these victims and contemplating the scale of the human tragedy that affects not just these people, but also their friends and relatives. It is jarring to reconcile the happy face of a twenty-year-old with the reality that she was abducted and tortured, and quite possibly drugged and thrown from a military aircraft into the Atlantic, never to be seen again. These faces belong to the disappeared, and like their family and friends, we, the viewers of the “Muro”, do not know what ultimately became of them. There is no closure in these pictures. There can’t be.

But the “Muro” takes advantage of its web-based format, adding a second level to this exercise in historical memory. Each image is hyperlinked to a specific page dedicated to that victim. These victim pages contain sparse information about the person: their name and their age, the date they were detained or disappeared, the last known sighting of the victim, and, when available, the case number assigned to the victim by the post-dictatorship government’s pioneering truth commission. Many of the victims’ pages contain some brief biographical background: He worked in a factory, she studied arts, he was married. Some pages feature additional photos contributed to the project by friends and relatives. At the bottom of each victim’s page, a small box features the following text with a hyperlink to the project’s email address embedded in the last phrase:

Did you know Marta?

If you knew Marta, or if you want to share your memories or any information about her—or if you know what happened to Marta after her disappearance—please, write to us.2

This invitation to interact with the “Muro” is an instance of the active memory that sustains the Argentine memory movement. Undoubtedly, this sort of engagement is a focus of the constituent organizations of Proyecto Desaperecidos. But the “Muro” is also an exercise in restoring dignity to these debased victims: it is a silent tribute to the victims of the dictatorship, and to their relatives and friends. The “Muro” also functions as an invocation of the unresolved nature of disappearance, and a reminder of the special anguish that this crime inflicts on the friends and family of the victims. Though loved ones harbor few illusions about the possibility of the disappeared ever being found, very occasionally some victims have resurfaced and reconnected with their relatives.

This may be part of the reason that the appearance of the individual victims’ pages differ from that of the “Muro”. Dispensing with the bleak black and white and ordered rows of the main gallery, the victims’ pages are often colorful and the arrangement of items is more individualized. Subtle though it is, there is a shred of hope here amongst so much despair.

But, having noted that tinge of optimism, it must be stated that the overall effect of the “Muro de la Memoria” is quite devastating. To look at the faces of these 1,300 people—a fraction of the total number of victims of the Argentine military dictatorship—is to play witness to a great, ongoing tragedy. In remembering these victims through the “Muro”, we are also induced, on some level, to identify with them, to imagine them when they were free—the victims are not yet victims in their portraits. But collected and connected together in this memorial, we are also forced to consider the fates of those candid, contented faces, and those pensive, pondering visages. This can be a harrowing, even numbing, experience. We see lives that have been rescinded, redacted, erased, eliminated. In the photos and texts, we understand the awful ambiguity of disappearance for those who are left behind—the secondary victims that have to live with not knowing.

And while looking at the “Muro”, we are compelled to remember and echo the sentiment expressed by the title of the Argentine truth commission’s report into the disappeared, Nunca Más. Never Again. We want to believe that such crimes will never again occur, but we know that even now, as we stare at these faces from an increasingly distant moment in Argentina’s history, similar crimes are being repeated in the world. It is for that reason, more than any other, that the “Muro de la Memoria” was created, and for that reason that it is so important.

Notes

- Statement from: http://www.desaparecidos.org/arg/eng.html

- The text is the same for each victim. Only their names change. For Marta’s page, see: http://www.desaparecidos.org/arg/victimas/e/esain/

Muro de la Memoria (Wall of Memory)

Online Gallery, Muro de la Memoria

Proyecto Desaparecidos (ongoing)