Memory

Maria Claudia

A plaque in the pavement commemorates Maria Claudia Falcone, a 16-year-old high school student and activist disappeared by the Argentine military dictatorship of 1976-1983. The plaque is an example of Argentina's active memory culture. It reads, in part:

Kidnapped in La Plata during the 'Night of the Pencils'.

1999 – EMEM 7 school renamed after her.

Educational Community of the EMEM Schools and Neighbourhoods for Memory and Justice.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

July 2015

Olympus TG2

Gertrud

A Stolperstein (stumbling stone) embedded in the pavement outside a flat in Berlin.

Begun in the 1990s by German artist Gunter Demnig, the Stolpersteine mark the last place of residence of those persecuted by the Nazi regime and share basic details of that person's life. Over 75,000 Stolpersteine have been placed in numerous countries, and the project continues. This one reads:

Here lived Gertrud Baruch.

Born in 1876.

Deported 24 Oct 1941 to Łódź / Litzmannstadt.

Murdered 4 May 1942.

Berlin, Germany

November 2014

iPhone 5S

Gertrud

A Stolperstein (stumbling stone) embedded in the pavement outside a flat in Berlin.

Begun in the 1990s by German artist Gunter Demnig, the Stolpersteine mark the last place of residence of those persecuted by the Nazi regime and share basic details of that person's life. Over 75,000 Stolpersteine have been placed in numerous countries, and the project continues. This one reads:

Here lived Gertrud Baruch.

Born in 1876.

Deported 24 Oct 1941 to Łódź / Litzmannstadt.

Murdered 4 May 1942.

Berlin, Germany

November 2014

iPhone 5S

Gratitud

Plaques expressing gratitude to Archbishop Oscar Romero fill a low wall outside the chapel where he was murdered. Renowned for his embrace of the poor, and an outspoken critic of the Salvadoran government and widespread human rights abuses in his country, Romero was shot and killed by right-wing death squads while conducting mass on 24 March 1980.

San Salvador, El Salvador

March 1997

Pentax IQ Zoom 120

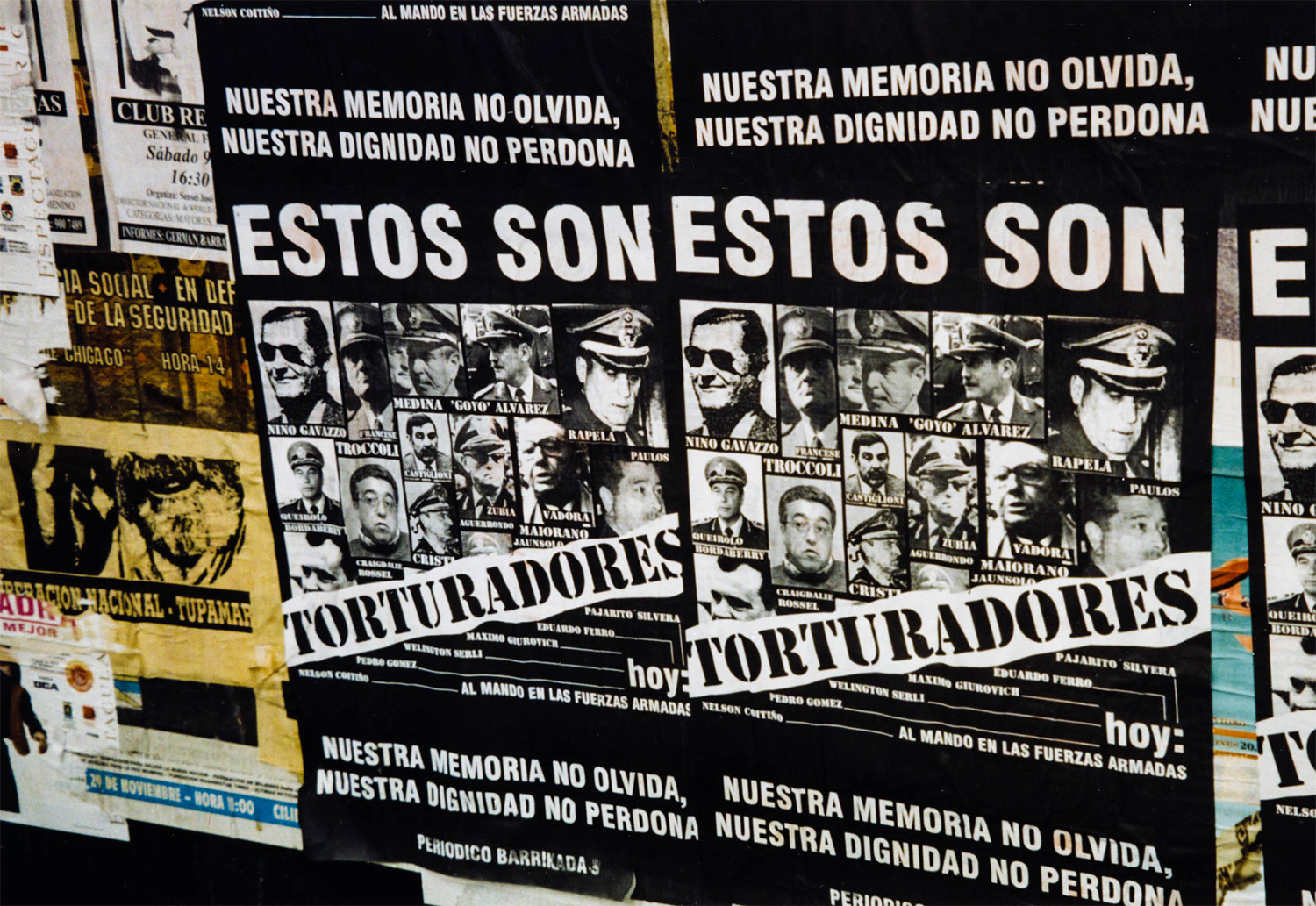

Estos son torturadores

Posters in Montevideo denounce current military figures for their role in the country's 1973-1985 military dictatorship: These are torturers. Our memory won't forget, our dignity won't forgive.

Montevideo, Uruguay

May 1998

Pentax IQ Zoom 120

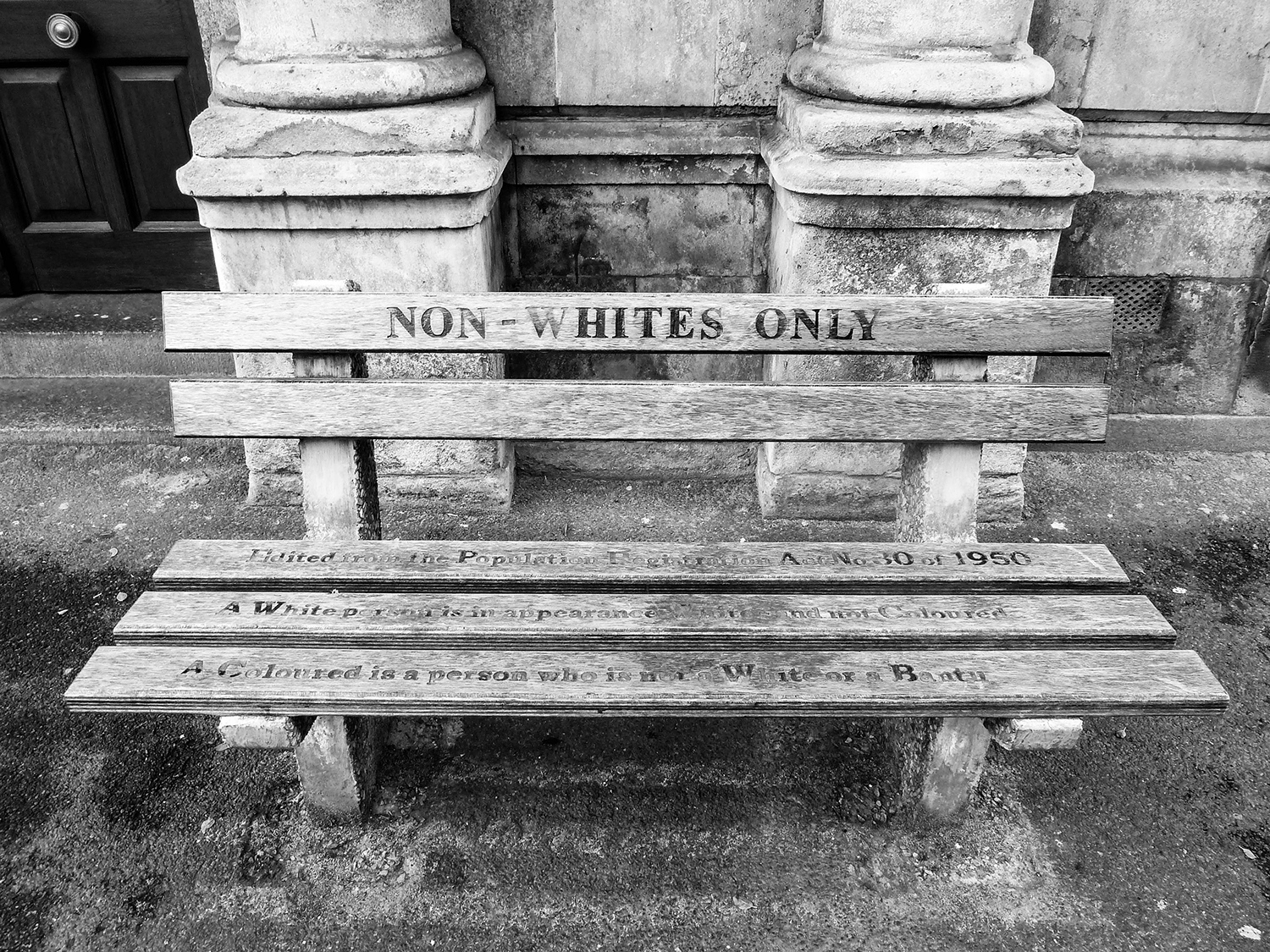

Non-whites only

As part of a memory project, artist Roderick Sauls installed two replica Apartheid-era benches outside the High Court Annex in Cape Town in 2007. It was here that race classification hearings took place based on the Population Registration Act (in effect from 1950 to 1991). A second law, the Separate Amenities Act of 1953, ensured the pseudo-mantra of 'separate but equal' by installing facilities like benches and water fountains designated 'Whites only' or 'Non-whites only'.

Sauls' benches quote precise definitions from the legal text as a reminder of the fallacy, and provoke quite a reaction when stumbled upon...

Cape Town, South Africa

July 2010

Panasonic DMC-TZ10

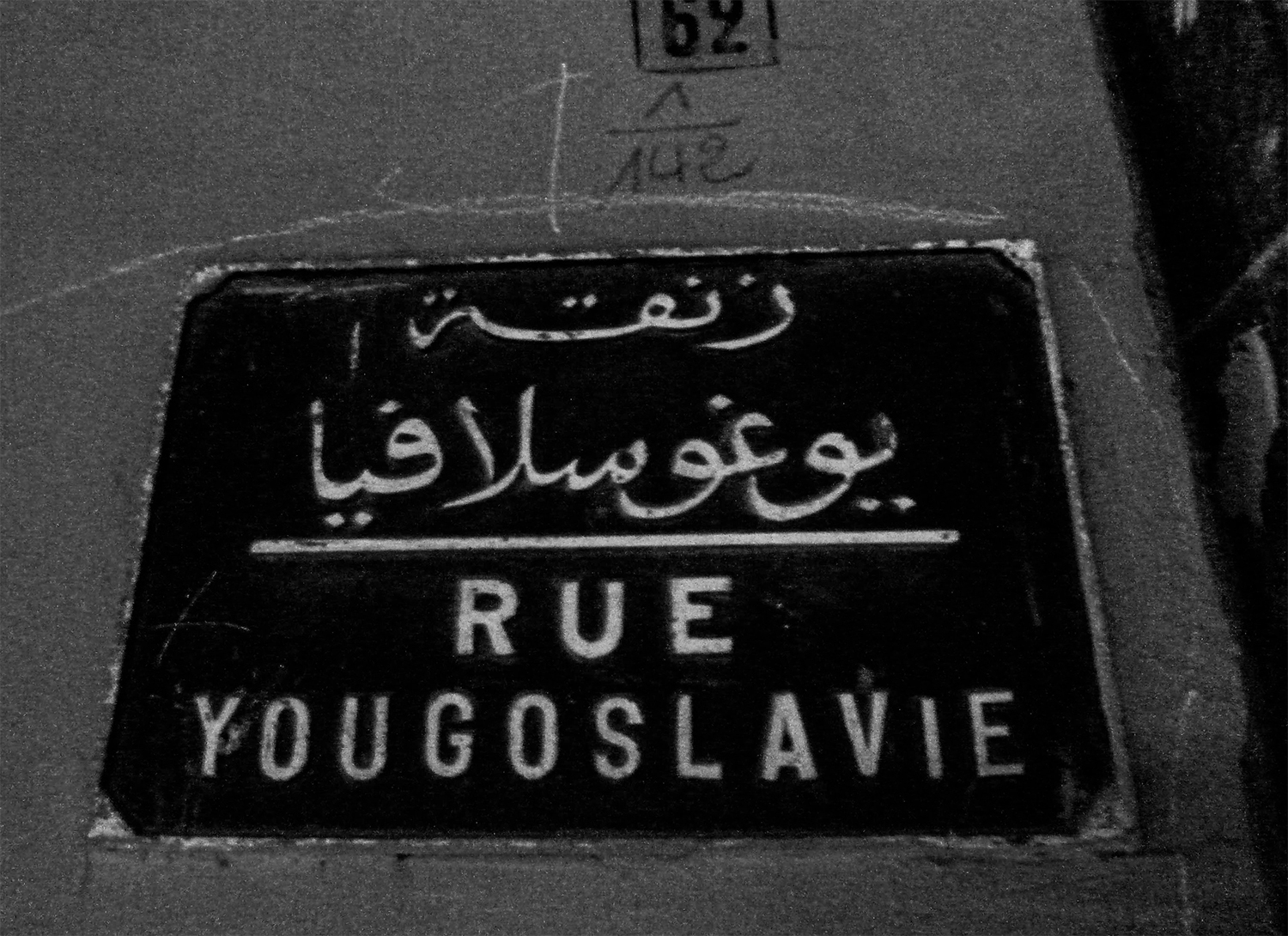

Rue Yougoslavie

An old street sign in Marrakech's Guéliz quarter preserves the name of Yugoslavia, a country that is no longer with us. The street has carried the name since Moroccan independence in 1956. Previously, it had also been associated with the Balkan state – named Rue Alexandre 1er to commemorate the Yugoslav king gunned down in the streets of Marseille in 1934.

I'm still undecided if that is some sort of tribute to Yugoslavia's passing scratched into the concrete around the sign.

Marrakech, Morocco

December 2010

Panasonic DMC-TZ10

Guerra civil

A mural in San Salvador depicts the suffering and scale of the 1979-1992 civil war that had concluded in a peace agreement just a few years earlier.

San Salvador, El Salvador

March 1997

Pentax IQ Zoom 120

1976

A mural commemorating the disappeared victims of the 1976-1983 military dictatorship in Argentina.

Attempts to deface the mural show the staying power of the country's reactionaries – between the 9 and 7 some fascist even scraped AAA, acronym of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance, a far-right death squad that emerged in the late Perón years and murdered some 1100-1500 people. Argentina's post-dictatorship judiciary later found the AAA guilty of crimes against humanity.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

May 2004

Pentax Espio 24EW

No se olviden de Cabezas

An outline commemorating the Argentine journalist José Luis Cabezas, who was kidnapped and murdered in 1997 while investigating a gangster with links to the country's then-president, Carlos Menem.

Cabezas' murder became an emblematic symbol of corruption at the top levels of government, and the popular slogan 'Don't forget Cabezas' an expression of the public's dismay at official impunity.

Buenos Aires, Argentina

July 1999

Pentax ZX-M

Potsdam trompe l'oeil

With the camera positioned just so, this neoclassical cupola appears to sit proportionally atop a modernist base in the heart of Potsdam. It kind of works.

They are, though, two separate buildings. The dome belongs to the St. Nicholas Church, which dates from the mid 19th Century when Potsdam was part of the Kingdom of Prussia. In the foreground is the facade of the Institut für Lehrerbildung 'Rosa Luxemburg', a teacher training academy built in the 1970s when Potsdam was part of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany).

This view no longer exists.

A 2010 decision by Potsdam city officials ordered the dismantling of the Institut, which duly occurred in 2017. It is to be replaced by a new structure that will recreate the facade of Prussian palace while masking a contemporary interior – the rationale being to create an architecturally harmonious setting on a key central square.

Sound familiar? Berlin also recently opted to remove the DDR-era modernist Palast der Republik (itself built on the site of a Prussian palace the East German government had demolished for its symbolic associations with the imperial past) and erect a simulacrum Prussian palace (the Humboldt Forum project).

These decisions – which evoke one history while erasing another – are a continuation of Germany's highly contested reckoning with its past, as Brian Ladd explores in his excellent book, Ghosts of Berlin: Confronting German History in the Urban Landscape. For some, the frequent consensus for neoclassical lines among politicians and urban planners is a canny dodge reflecting a certain conservatism – it seeks to escape the extremes of the 20th Century (including their manifestations in architecture) by locating historically safe ground in the perceived unity of the imperial Germany of the Kaisers. But that preference is a hagiographic illusion (the clue is in the word 'imperial'), and opts for an allegorical amnesia over a challenging architectural response to the complexity of the German experience.

There is something incredibly uninspired (not to say regressive) about rebuilding long-gone imperial palaces on sites where the ground is both hallowed and historically contested. And as beautiful as neoclassical facades may be (and Berlin and Potsdam have plenty of them to show off), as 21st Century new-builds they are dated symbols that fail equally at capturing nuanced historic legacy and at presenting the forward-looking aspects of contemporary German society.

Potsdam, Germany

September 2010

Panasonic DMC-TZ10