Araucan Nightmare: Life and Death in Tame

An intimate portrait of a small town at war in Colombia's east.

This text originally published: 5 August 2003

Introduction

On Friday, June 6, 2003, around 5 PM a Chevrolet LUV was making its way toward the center of Tame, a town of 25,000 on the plains of the war-ravaged department of Arauca in eastern Colombia. The truck was packed with explosives, and, according to local officials, a few extra, atypical ingredients. Arranged around the explosive device were four canisters containing a mixture of gasoline, ammonia, what authorities suspect was sulfuric acid, and an adhesive known as boxor. This chemical cocktail was intended to augment the effects of the explosion, with the glue enhancing the capacity of the flames to stick to whatever they landed upon.

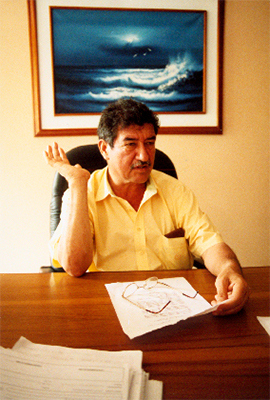

Acting on a tip from local informants, the car bomb was intercepted by the Colombian army before it reached its target. The driver was questioned and said he had been offered money and pressured by presumed guerrillas to park the van near a police post.1 The army technicians who defused the bomb estimated that it had a blast radius of four to five blocks. “It would have finished off the church, the mayor’s office, the police station, and all the people working around here, the people living in these blocks. This makes you think, ‘If that many children had died, if there were hundreds of dead, where people who identified with them or identified with us or with some other institution or who we don’t even know who they identified with [would have died], this would be a truly indiscriminate act,’” a pensive Tame Mayor Jorge Bernal said. “It would be a serious crime against humanity. It gives a sense of the absurd war we are living through. Were they trying to solve some problem by killing this way?”2

Had the bomb gone off, it would have been a severe test for one of the Colombian state’s experiments in what is universally referred to as ‘Public Order.’ In the past two years, Tame’s once short-staffed police station has seen a five-fold increase in manpower while also being reinforced by a special urban deployment from the local army battalion. Tame’s urban center is now guarded by as many as 200 heavily armed soldiers and police at a time, resulting in a marked decrease in guerrilla attacks on the town. Undoubtedly, the bomb would not have won much sympathy from the local population for the guerrillas that had sent it. But it would have sent a message to the large police and army contingents in the town center, as well as to the paramilitary forces that have usurped the Tame neighborhoods that were once guerrilla territory: your experiment isn’t working, you are not secure.

Tame Changes Hands

Tame police station damaged by FARC cylinder bomb. Photo: Eric Fichtl

Until recently, the municipality of Tame was firmly in the grasp of Colombia’s two largest guerrilla groups, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). The FARC’s 10th and 45th Fronts and its Alfonso Castellanos Mobile Column (numbering some 2,000 fighters in total) and the ELN’s Domingo Laín Front (with as many as 2,000 fighters) had the state forces seriously outgunned in the Arauca department. In Tame, the national police had just 20 men for a town that, at the time, had a population of upwards of 30,000 people. Like the current situation in nearby Saravena (see, The Battle for Saravena), the police could do little more than hunker down in their bunker-like station and hope for the best.

The guerrillas attacked the police at will, firing rifles across the town square at the station, hurling grenades at patrolmen, and launching cylinder bombs that leveled a building next to the police station and blew the front roof off the station itself. During 2000, the bombings were monthly. In all, more than 32 police in the Tame municipality were killed between 1993 and 2003, the highest number in all of Arauca. Despite the presence of the Colombian army’s 18th Brigade and its Navos Pardo Battalion on the outskirts of Tame, the municipality was effectively guerrilla territory, as it had been for decades.

For the guerrillas, control of Tame had important benefits. They levied “war taxes” on local businesses, ranchers, and farmers, providing a significant source of revenue for their insurgencies. Territorial control also meant political influence, as the guerrillas could lean heavily on local elected officials and drive their spending decisions, no small perk considering the fact that in oil-rich Arauca 9.5 percent of oil revenues were administered by the departmental government, at least until the Uribe administration revoked that right earlier this year. The guerrillas even undertook infrastructure improvement projects during their hold on Tame, stealing machinery to construct roads.3

In 2001, however, the guerrillas’ free rein in Tame was challenged by the right-wing paramilitaries of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). The AUC’s Bloque Vencedores de Arauca (Arauca Vanquishers’ Bloc) moved about 450 of its fighters into Tame to try to dismantle the guerrilla hold on the municipality. They coalesced with certain local ranchers and politicians who had been victimized most by the FARC and the ELN. Facing continued harassment from the army in the rural sector and the new encroachment by the paramilitaries, particularly in the urban areas, the guerrillas changed tactics, pulling most of their forces from the town’s neighborhoods and retreating to the plains and riverine jungles in the rural sector of Tame and deeper into Arauca where they would regroup and pursue new strategies.

Tame Mayor Jorge Bernal holding a fax from the FARC naming him as a 'narcoparamilitary'. Photo: Eric Fichtl

The paramilitaries, meanwhile, surged into Tame in numbers not seen elsewhere in the department. As is all too common when territory changes hands in Colombia, upon gaining control, the paramilitaries went about eliminating those they felt had collaborated with the guerrillas during their reign in Tame. The guerrillas responded in kind, and civilians were caught in the middle. Lifelong tameños have been given the option to leave town or be killed or kidnapped. Carrying out simple, daily activities can be construed as aiding one group or another, depending on who sees what and informs whom. Killings, reprisal killings, and counter-reprisals have become the order of the day. As the local judge explains it, “None of these groups has… respect for human rights. They kill children, women, the elderly, at whatever time of day, in the presence of whatever person, in whatever way, slashing with knives, chopping with machetes, shooting people countless times, and even burning people alive.”4 According to the commander of the National Police in Tame municipality, Lt. Col. José Antonio Lopéz, the FARC, the ELN, and the AUC share the responsibility for the murders in Tame’s rural sector, while in the urban area, “Those who are most violating human rights are the [paramilitary] self-defense groups. Although we have seen homicides by the FARC and the ELN, these are a minority.”5

This wave of selective assassinations and forced disappearances from 2001 onward have made Tame one of the most violent municipalities—if not the most violent—in Colombia. In the past two and a half years, more than 300 people have been killed in the municipality, which a few years ago numbered 80,000 inhabitants but has dwindled to between 60,000 and 70,000 as a result of conflict-generated displacement. By June 11 this year there were already 131 murders in Tame, a homicide rate about 66 times the annual U.S. national rate.6 Authorities point out that this count excludes the as yet undetermined number of victims buried in suspected mass graves, especially in Tame’s rural sector.

According to a local army official, an estimated 70 percent of Tame families have had at least one victim of the violence.7 A local priest concurs, “The truth is that there are families here that are completely destroyed. There are families that have seen two or three of their children killed simultaneously.”8 Not surprisingly amid this bloodletting, a climate of fear has beset the people of Tame. The local Fiscal, a state official in charge of criminal investigations, has had only one witness to a murder come forward during his 16 months in Tame. Frustrated, he admits, “The people know who’s doing the killing… They know, but it’s the law of silence.”9 The straight-talking local judge puts it a different way: “The people stay silent out of fear, because here you can’t open your mouth much—if you open your mouth here it will fill with flies.”

Garrison Tame: An Experiment in Public Order

Alongside the arrival of the paramilitaries and the “selective cleansing” of Tame, there has been a significant build-up in the capacity of the state forces. In September 2002, the police contingent increased its size from 20 to 120 men.10 At the same time, plans were underway for the army’s 18th Brigade, historically focused on fighting guerrillas in the countryside, to be reinforced by another unit, thereby freeing up some of its own forces to work on securing Tame town. The Colombian army’s newly created, U.S.-supplied rapid deployment force, or FUDRA, was stationed at the 18th Brigade’s Navos Pardo Battalion base on the outskirts of Tame in early 2003, and after moving on to another conflict zone was replaced in April 2003 by the 5th Mobile Brigade, troops of which are daily engaging in combat with the guerrillas, and at times paramilitary forces, in the countryside. The arrival of the 5th Mobile Brigade increased the army presence in Tame municipality to some 4,000 men, according to the local police commander, which enabled the 18th Brigade to dedicate part of its resources toward establishing a permanent presence in the center of Tame.

Tame police conduct a round-up of unfamiliar faces. Photo: Eric Fichtl

The head of the new urban deployment is Captain Paredes of the army’s 18th Brigade. From a second storey office overlooking Tame’s tree-filled central plaza, he coordinates the activities of the company of approximately 150 soldiers patrolling the town’s streets. He is also active in various outreach programs the military conducts in order to win over the locals. Capt. Paredes points out that the army has a lot of catching up to do in the struggle for the hearts and minds of the people, given that the Navos Pardo Battalion has existed for just seven years as opposed to the thirty years of guerrilla influence in the region. He sums up the “Integrated Action” the army is using to that end: “The specific mission converges in two areas. One is the military presence… including attacking the illegal groups, be they guerrillas, self-defense groups, or militias in the town center, and also narcotraffickers… Aside from our military operations, we also have to work on psychological operations. These essentially say to the community, ‘We must invest in security in order to have social progress, because without security no one invests.’”11

That security is provided by flooding the town center with soldiers, creating a virtual garrison. Better supplied than the National Police, the soldiers stand guard day and night on Tame’s central streets and plaza, at local government offices and at the town’s small airport. It is no exaggeration to say that the Colombian soldiers and their Israeli Galil rifles are never out of sight in the town center. They enforce road blocks on some of the streets around the plaza to control traffic, and by night they extend their security cordon to envelope several square blocks in the center of town. In conjunction with the National Police, the army conducts sweeps and patrols of the outlying neighborhoods to check the identity and activities of anyone they don’t recognize, to look for stolen vehicles (universally favored for car bombs), and to make their presence felt.

Among the psychological operations the army mounts is the “Soldado por un Día” (Soldier for a Day) program, employed elsewhere in Arauca, which uses inducements like clowns, candy, and a trip to the military base to illuminate for children—and sometimes adults—the ways of the army, while also encouraging the “soldiers for a day” to inform on any suspicious activities. Army officials also give talks on democracy and respect for the national symbols to schools and community organizations, and at times the soldiers hand out propaganda fliers encouraging members of the illegal armed groups to turn themselves in. The army has organized a sports league that encourages locals to come to the base to play, and they have occasionally brought doctors and dentists to neighborhoods to provide services. Says Capt. Paredes of the outreach, “We can’t solve all their problems… But we do what we can, we collaborate… so they don’t have to go to the guerrillas for help, or to the self-defense groups. Rather, we want them to come to their public forces, their army.”

Two soldados de mi pueblo on sentry duty in Tame. Photo: Eric Fichtl

Part of the strategy that induces locals to trust in and collaborate with the army is a new program initiated by President Uribe’s administration in January 2003. Called “Soldado de mi Pueblo,” or “Soldier From My Town,” the program inducts locally born and raised men into the military for service in their own communities. In Tame municipality, there are 36 “soldiers from my town” on active duty, and plans are afoot to draft more. Twenty-one of these soldiers are among the company of 150 or so troops charged with guarding Tame’s town center, while the other 15 serve in Tame’s rural sector. The fact that these new soldiers are locals themselves means they are easily recognized by the townspeople, providing a distinct intelligence advantage to the army. As one soldier from the program says, “We try to get our relatives and friends to bring us information about what the guerrillas are doing… Any remarks or gossip about a kidnapping or a theft or that the guerrillas are going to harass someone, we know in a moment. This is what we do: receive information and pass it to our commanders, so that we can take security measures and counteract what the guerrillas are planning.”12 In contrast to the more polished pronouncements of their commanding officers, who routinely remember to include the self-defense groups in their condemnations, the two recently inducted “soldiers from my town” this writer met with shared a narrow focus on the guerrillas as their enemy, despite the fact that in Tame town the majority of all murders are committed by the paramilitaries, a fact Tame’s police commander readily acknowledges.

These civic-military operations, the “Integrated Action” in the army’s words, have had results in Tame’s town center. The sheer quantity of soldiers discourages the guerrillas from attempting a frontal assault, although, as the foiled car bomb plot demonstrated, not from less direct challenges to the military presence. Local shops are open for business, people walk and drive around relatively uninhibited compared to the conditions in other Arauca towns, and according to Capt. Paredes, there has not been a single successful cylinder or car bomb attack in the center since the army arrived. That’s not for a lack of effort, though, because during his two years in Tame, the captain says he has deactivated 32 explosive devices, four car bombs, and a motorcycle bomb.

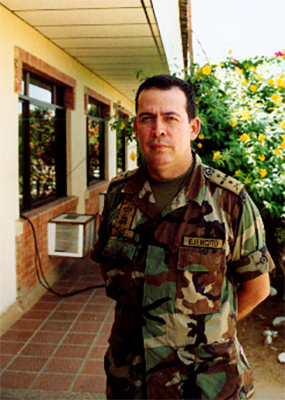

Capt. Paredes grows especially proud as he describes the fact that his troops were able to secure a nearby river bank so that locals could hold their traditional picnic there for the first time in seven years, despite guerrilla threats to disrupt the proceedings. Colonel Cruz, Commander of the 5th Mobile Brigade stationed at the Navos Pardo Battalion just outside Tame, agrees: “Here what we are constructing is social fabric, we are making democracy. We are supporting the programs of the mayors in the sense that we are giving them the minimum security necessary for them to realize social investments in the urban and rural areas.”13

But the efficacy of the strategy is limited. By all accounts, effective control of Tame has passed from one illegal armed group to another despite, or perhaps enabled by, the beefed up military presence. As noted earlier, the murder rate in Tame is exceedingly high, and there is complete impunity for the killers. The Uribe administration seems to have gambled that its Soldier From My Town program would provide enough recruits to flesh out the urban security forces while freeing up the army’s special mobile brigades for intensified campaigns against the guerrillas in the surrounding countryside. As one “soldier from my town” sees it, “The program we have here in town is almost an imitation of the police, because we live in the urban area and normally we don’t go out to the rural areas. We are looking after the town. The police do the same thing. They watch the town—they’re responsible for public order.”14 However, unlike the police, who are not from Tame and live fulltime in the fortified police station, the “soldiers from my town” often live at home with their families. It has yet to be seen whether the guerrillas will start to target relatives and friends of these soldiers the longer the program runs, but the nature of Colombia’s dirty war suggests they may adopt just such a tactic.

Tame is a testing ground for the program, but it’s implausible that the model could be expanded to all of Colombia’s Tame-sized or larger municipalities: the expenditure for training thousands of new “Soldiers From My Town” would be immense, and the additional commitment of regular troops to urban guard duty would severely diminish the field capabilities of the Colombian army. Whether this will work remains to be seen, but without a doubt the Tame experiment is being watched by officials in Bogotá. One limitation already seems clear: Tame’s Mayor points out that just about all the state and departmental resources he receives are war-oriented, neglecting other important needs: “Without security there is nothing—but we also need the social investment component, the integral parts of which are education, health, roads, and electricity.”

Rural Tame’s Tragedy

The plains surrounding Tame. Photo: Eric Fichtl

For now, though, there is a striking disconnect between Tame town and its immediate, rural surroundings. At the edge of town, state authority dwindles. Guerrilla checkpoints surround the town and control its inbound and outbound traffic. Locals refer to the guerrillas as “los de abajo,” or, “the guys down there,” just outside town. According to Lt. Col. Lopéz of the National Police, despite the increased state presence, “The public forces have not been able to control the violence” between the illegal armed groups, the majority of which rages in the countryside all around Tame. The people in town feel stranded, as if they were living on a tiny island in a violent sea. As the Mayor puts it, “We are in a trap here, a trap we can’t move around in. We can’t even go to the various neighborhoods of the town, let alone to the countryside.”

If life in the urban area feels penned in, life in Tame’s rural sector is even more intense. The FARC and the ELN remain dominant in the countryside around Tame, but in recent years they have been confronted increasingly by both the AUC and state forces. The guerrillas and the paramilitaries are now in an all-out war for control of territory and resources in the region. As one tameño civilian points out, “The economy is in the countryside, and the countryside is run by the guerrillas. Whoever runs the countryside runs the economy.” All involved in the conflict are keenly aware of this reality.15

The turmoil that rural communities in Tame and elsewhere in Arauca experience is exemplified by an incident at the indigenous reserve of Betoyes, composed of a number of small hamlets near Tame. In early May this year, an armed group attacked the indigenous Guahibo community at Betoyes. Three Guahibo girls, ages 11, 12, and 15, were raped by the assailants. A pregnant 16-year-old, Omaira Fernández, was also raped, and then the attackers reportedly cut her womb open to pull out the fetus, which they hacked apart with machetes, before dumping her body and the fetus in a river. That same day, three indigenous men were shot and disappeared. Some 327 of the remaining Guahibos fled the reserve for Saravena, a town in the northwest corner of the Arauca department. Once there, the Guahibos took up residence in an abandoned school, protesting their displacement by occupying a church.

Witnesses say that soldiers from the Colombian Army's Navos Pardos Battalion disguised themselves as AUC paramilitaries before committing atrocities at the Betoyes indigenous reserve. Photo: Eric Fichtl

Who attacked, raped, murdered, and displaced these Guahibos? Almost all accounts point toward soldiers from the 18th Brigade’s Navos Pardo Battalion—the same group providing security to Tame’s town center—perhaps working in conjunction with the paramilitaries. On May 14, the Regional Indigenous Council of Arauca (CRIA), a departmental indigenous organization affiliated with the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), reported that a number of survivors from the Betoyes massacre identified the attackers as army troops wearing paramilitary armbands. The same day, the Joel Sierra Committee, an Arauca human rights group, echoed the claims in a press release signed by a number of regional NGOs.

In a June 4 release, Amnesty International (AI) reported that army helicopters had strafed and bombarded a number of the hamlets that make up the Betoyes reserve during a late-April skirmish with guerrillas; their sources also indicated that the choppers had ferried in army troops as well as paramilitary fighters. Then, on May 1, according to AI, soldiers from the 18th Brigade entered a number of Betoyes hamlets wearing armbands from the AUC and the paramilitary Self-Defense Forces of Casanare (ACC), a splinter group that has refused to participate in AUC negotiations with the government. During a similar attack by a group of armed men in Betoyes in January 2003, witnesses said that the AUC armband of one attacker slipped to reveal the words “Navos Pardo Battalion” printed on the uniform beneath.

Evidence that the attack was carried out by paramilitaries acting alone is hard to come by. Reporting from Saravena, Reuters correspondent Jason Webb interviewed a survivor of the May attack on Betoyes who said, “The paramilitaries told us if we didn’t leave town, they would make us kneel down, massacre us, and rape us.”16 But considering the plethora of reports alleging the army’s use of AUC armbands as disguises, this witness’s account does not exclude the possibility that the attackers were members of the Colombian armed forces.

According to Darío Tulibila, president of the CRIA, during the May incursion, a number of the attackers wearing AUC armbands were identified by villagers as known members of the Colombian army—witnesses could even provide their names: Eran Alfonso Ríos Monterrey, Lisandro Camargo Acevedo, Diego Muñoz Usquiana, etcetera. Tulibila does not shy away from assigning blame for the Betoyes massacre: “It wasn’t the paramilitaries, it was the army. The army itself is creating the disorder.”17

The army has a different stance entirely. “It’s a disgrace to declare that what the terrorists have done was actually the army disguised as terrorists. It’s easy if you’re not here to echo such slanders… They are lies, not by Amnesty International, but by those who told them to Amnesty International. Amnesty International can’t come corroborate them in the field,” says an obviously perturbed Colonel Cruz, Commander of the Army’s 5th Mobile Brigade residing at the Navos Pardo Battalion base. His version of the events sums up the army’s position: The paramilitaries arrived in Betoyes in mid-April and confronted the FARC and ELN forces stationed there. In order to remove the armed groups from the area, the Navos Pardo Battalion then mounted Operation Colosso, “which had excellent results.” The nation’s leading newspaper, Bogotá daily El Tiempo, mostly parroted the army line, reporting in a May 15 article that the displacement occurred as a result of paramilitary confrontations with guerrillas in the area, and that civilian deaths had occurred in the “crossfire” between the groups.18

Colonel Cruz, Commander of the Army’s 5th Mobile Brigade. Photo: Eric Fichtl

However, Col. Cruz is even more focused in his account of the incident: “The terrorist groups of the FARC and the ELN forced, for some weeks now, a massive displacement of indigenous people and peasants from the area of Betoyes, where there are various indigenous reserves, and obliged them to move into some very difficult, subhuman conditions in the city of Saravena.” He says the army’s 18th Brigade and his 5th Mobile Brigade are now working to secure Betoyes so that the displaced Guahibos can return to their lands.

But the available evidence seems to contradict the army’s version of the events. The most striking hole in the official line is that the Guahibos, allegedly displaced by the guerrillas, fled to Saravena, the most guerrilla-controlled town in all of Arauca. This was hardly the place to go to avoid their purported attackers. According to Tame’s Mayor Bernal, in the immediate aftermath of the Betoyes massacre, some of the displaced Guahibos arrived in Tame seeking refuge, but quickly dislodged to Saravena because, “they said that in Tame they didn’t have sufficient guarantees. I offered them support so that they could stay in Tame, but they decided to go to Saravena and left.” It is illuminating to note that the Guahibos felt that their safety could not be guaranteed in Tame, home to the massive army and police security force and the largest paramilitary presence in Arauca, and that they felt guerrilla-dominated Saravena, hours away through heavily contested territory, was a safer place to seek refuge.

It is worthwhile noting, too, the comments of Colonel Montoya Sánchez of the 18th Brigade, who said that both the Guahibos occupying the Saravena church and other recently displaced peasants were following “ELN orientations.” That claim was vigorously denounced by the ONIC to Colombian Defense Minister Martha Lucía Ramírez: “[The colonel’s statement had] the evident goal of delegitimizing the demands of the displaced and automatically converting them into military targets.”19 The ONIC’s denunciation went on to contradict Col. Montoya Sánchez’s claims that the CRIA was being manipulated by the Joel Sierra Committee, a human rights NGO that military and public officials in Arauca often accuse of being a guerrilla front.

These Guahibos were displaced from their indigenous reserve at Betoyes in early May 2003. They fled to Saravena. Photo: Jason Howe

What is certain is that the displaced Guahibos are frightened and reluctant to return to Betoyes, despite army claims that it is securing the area for them. Jason Howe, a freelance photographer who traveled to Saravena in June, recounts a morning encounter he and a colleague had with some of the displaced Guahibos who were washing their clothes on a riverbank: “Their desperate flight from their homes had left them exhausted and frightened. Slowly, we moved towards them crouching in order to appear less of a threat, smiling until our faces hurt. Eight-year-old girls dressed in tattered dresses hugged naked, crying babies closer to the chests, eyes darting around trying to assess the danger. Our smiles were not returned; clothes and dirty children were hurriedly scrubbed. Wet clothes were stuffed into bags, the tiny babies strapped onto their mothers’ backs and without a backwards glance the refugees climbed the steep riverbank and returned to the smoky, filthy camps into which we were not allowed to follow.”20

This terrorizing of communities happens on a daily basis in the countryside around Tame. All armed participants in the conflict, across the political spectrum, contribute to the displacement. As the Bogotá-based research group the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES) notes, “Displacement isn’t a collateral effect of the war—it’s a central strategy of the war. It is entirely functional.” Worse still, says CODHES, is the fact that those who force displacement in Colombia continue to enjoy complete impunity.21

“Whoever Runs the Countryside Runs the Economy”

There are a number of economic factors driving the combat and displacement in the rural sector. For starters, the flat, open areas around Tame are considered some of Colombia’s finest agricultural and grazing land. Over the years, small and medium-sized fincas have provided decent livings to many campesinos in the Tame municipality, while ranchers have been able to raise mass quantities of livestock. But the intensified fighting has forced thousands of peasant families off their land, with all armed participants in the conflict causing displacement. “The people are caught here, like prisoners, because they can’t get out of the town to their fincas. It’s a truly delicate situation,” says Mayor Bernal.

According to local priests, some of the hamlets near Tame that they once ministered to are completely vacated. When the campesinos abandon their fincas, they go in a hurry, leaving their very means of survival behind them. There are nine camps of internal refugees in Tame. Bernal describes their plight: “Displaced people are constantly arriving here… These people don’t have roofs—they have nothing. The situation has been very difficult.” Others have gone further afield, joining the hundreds of thousands of displaced people in cities like Bogotá. Tame’s ranchers have often had their livestock stolen by the guerrillas, who have at times turned the animals over to peasants but more often sought to trade them for legitimate livestock and other supplies just across the remote and uncontrolled Venezuelan border. Ranchers, too, have been forced to flee, with many making for the relative safety of Bogotá.

Tame is considered the gateway to Arauca from the interior of the country, which has lent an element of speculation to the territorial warfare. Located along the path of a planned highway that would connect Bogotá and Caracas, Tame is just around the point where travelers and transporters would need to stop for meals and refueling when Venezuela-bound.22 Whether such a highway would ever be built as long as the guerrillas remain in control of large swathes of Araucan land seems dubious, but for many of those who stand to gain should the project come to fruition therein lies the motivation to displace small landowners and help drive the insurgents out, usually by aiding or joining the paramilitaries.

The logo of the Navos Pardo Battalion. Photo: Official Photo

Petroleum is another factor at play in the territorial warfare in Arauca. The department’s oil fields and its Caño-Limón pipeline, operated in part by U.S.-based Occidental Petroleum, generate significant wealth—when they are functioning. Until recently, when the Uribe administration changed policies in favor of greater central government control, the departmental government of Arauca was in charge of administering 9.5 percent of the royalties generated by the department’s oil fields. By establishing a dominant presence throughout the region, an armed group could exert serious influence over the spending of the oil revenues within each municipality, not to mention the possibilities for more direct forms of graft.

Likewise, by bombing pipelines and oil installations, the guerrillas routinely affected oil revenues, demonstrating a capacity to interrupt the business agenda of the Colombian state and its multinational partners. These attacks, including 170 bombings of the Caño-Limón pipeline in 2001, were instrumental in bringing about the arrival of U.S. Special Forces troops in Saravena, with the task of training Colombian soldiers in counterinsurgency and the protection of the oil assets. So central to the economy of Arauca is oil that the logo of the Navos Pardo Battalion is an oil derrick guarded by a soldier. Though Tame municipality is not at the center of the Araucan oil fields, it borders on those areas, lending it a territorial value of its own.

Another resource being exploited by the paramilitaries and the guerrillas is coca, the plant that provides the basic ingredient for cocaine. Recent years have seen an explosion in coca cultivation in the Arauca department, with the FARC considered to be the chief force behind the surge. Many peasants have been forced by the armed groups to replant their fields with coca. Three years ago, some 978 hectares of land were thought to be under coca cultivation in Arauca department. Estimates now put that figure between 12,000 and 18,000 hectares,23 a direct result of Plan Colombia’s fumigation “successes” in southern Colombia leading to the displacement of coca cultivation to new areas of Colombia, as well as across the border into Peru and Ecuador.

Police commander Lt. Col. Lopéz suggests that the paramilitaries are having a relatively easy time asserting themselves in Tame in part because the guerrillas are retreating toward the Venezuelan border, where aside from the black market trade in stolen livestock and other goods, they can slip vast quantities of cocaine into Venezuela, from whence it heads north to the U.S. market. He argues that, “The advance of the self-defense groups toward the Venezuelan border is to cut off the FARC’s narcotrafficking business. This is the war: the war between the extreme right and the left is for coca cultivation, which is what gives these groups their highest profits.”

Thus far, there have been no fumigation campaigns in Arauca, a noteworthy contrast to the situation in other departments with high levels of coca cultivation like Putumayo and Caquetá. But during the gimmicky three-day transfer of the capital from Bogotá to an Arauca military base in mid-July, President Uribe said it was imperative that fumigation begin in Arauca soon, adding, “Violent groups still feel strong here because they get money from drugs. To defeat them, we must cut off this trade.”24

What Future for Tame?

Students at the Hogar Juvenil, Tame. Photo: Eric Fichtl

At the Hogar Juvenil Campesino, a pilot school at the edge of Tame town, a novel program teaches campesino children and adults the necessary skills for a future on their farms, rather than away in the shantytowns of the big cities. Founded in 1993, the school started out with a class of 13 students. There are now over 90 fulltime students who come from the rural sector of Tame and live on the school’s idyllic campus during the week, returning home to their villages on weekends (if the conflict allows). Another 100 or so child and adolescent students attend classes on weekends, while on Sundays the school teaches over 110 adult students as well. All of the students are working toward a degree in Rural Wellbeing.

While providing elementary through high school education, the program focuses on teaching eco-friendly, sustainable agricultural practices, crafts like furniture-making, and strategies for bringing produce and products to market more successfully. The Hogar Juvenil tries to teach methods that will allow campesinos to stay and thrive in the countryside, without feeling forced to offer themselves up as cheap labor in the big cities. Students learn new agricultural techniques on the school’s test plots, harvesting crops that are in turn used to feed the students.

The Hogar Juvenil wages a noble fight against the odds, though, as the violence in the countryside impacts everything the students and the schools do. Many of the children are victims of the violence—some 30 percent of the current students are from displaced families. Further, the territorial war between the armed groups has totally disrupted the rural economy that the school’s students would return to, dramatically limiting the possibilities of the graduates to implement the practices they have studied. And the non-profit school is facing a budget crisis, continually taking on needy students, many of whom receive tuition-free schooling. Almost half of the school’s students cannot afford to pay tuition, an indicator of the rural poverty in the conflict zone when one considers the fact that monthly fees run about $30 per student.

In many ways, the school’s lonely struggle highlights the isolation and tragedy of life in Tame. Trying to convince peasants to stay and work the land they were born on, to ignore the lure of perceived wealth and (relative) security in the big cities, to stay and make Tame better—it’s an uphill battle at best.25 It’s a fight they may be losing: About 10 percent of school-age children in the Tame area are no longer able to attend school at all because of the conflict and threats to teachers. And since September 2002 there have been five teachers murdered in Tame, four of them by suspected paramilitaries.26

After guerrillas felled power lines, Tameños gather around a pizza cart with a generator to watch television. Photo: Eric Fichtl

Again and again in speaking with the people of Tame town, one hears of the overwhelming sensation of being trapped by the conflict. The isolation of this small town in Colombia’s eastern plains is complicated and multifaceted. The war raging in the countryside around Tame has made it an island, though one still very much afflicted by the violence. But sadly, for the most part the violence occurs below the radar of the Colombian media and public, and is certainly not making many international headlines. After receiving death threats from the armed groups, all of Tame’s journalists fled to Bogotá, leaving the municipality with no resident press to cover the daily carnage. The army’s radio station is the only one most tameños can tune in.

Independent verification of facts is difficult, as travel in the rural sector where most of the violence happens is extremely risky. In addition to the various armed groups’ roadblocks controlling much of the transit to and from Tame, FARC and ELN guerrillas routinely knock out the electricity and telecommunications towers that cross the nearby mountains, leaving Tame dark and cut off from the rest of the country. Often, the sound of generators rattling is the only sign of life after dark on Tame’s streets. As a local priest sees it, “The conflict in Tame has worsened in the last two years. We have no electricity, no communications, we can’t leave—we’re surrounded. Likewise, the people in the countryside can’t leave. I don’t know how long the situation will be like this.”27

On the governmental level, too, Tame feels abandoned. Mayor Bernal appreciates the increased security expenditures for Tame, but laments the lack of resources to deal with the problems his constituents confront. “The people can’t pay taxes to the municipality because—how? In the middle of a war that’s very difficult.” Compounding the absence of local resources are policy shifts from the Uribe administration, which has taken direct control of the proceeds of the Araucan oil industry, leaving funds for basic investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and education—not to mention resources to deal with the massive refugee crisis—severely lacking. Says Bernal, “The government has distanced itself from us quite a bit. It’s very difficult to speak with the high government. And the government of Arauca… since it doesn’t have the [petroleum] royalties, it can’t offer us any solutions. So they have practically left us on our own.”

In Tame, there are no guarantees. Every resident knows their actions are being watched, that they might be signing their death sentence by speaking with this person or being seen with that one. Two teenage boys summed up the tense situation in Tame succinctly when asked whether things had improved since the paramilitaries dislodged the guerrillas from the town center. The first boy answered quite matter-of-factly “It’s the same now as before.” Stunned by his friend’s frankness, the other teen nervously interjected, “We don’t talk about that because.…” As his voice trailed off he drew his fingers across his neck in the international symbol for “they’ll slit your throat.”28

Tame is experiencing some of the worst dirty warfare anywhere in Colombia. In fact, the army’s unique deployment in Tame’s town center might even be contributing to the bloodshed, in that they either collaborate with the paramilitaries by turning a blind eye to the selective assassinations or perhaps, if evidence from the rural sector is factored in, at times actively participating in the crimes. The paramilitaries, despite their much-vaunted negotiations with the government, show no sign of ending their campaign of “selective” slaughter. (see, What Cease-fire?). For their part, the guerrillas have not let up their campaign against Tame either: in early July disaster was narrowly averted when a “house bomb” in Tame was deactivated by the army, and two weeks later on July 22 the army intercepted yet another large car bomb. In the rural sector, all sides display a wanton disregard for human rights, hence the soaring murder rate and mass displacement throughout the municipality. Violence has truly become the norm for Tame’s people, and some generations have known nothing but war. One 13-year-old boy, fascinated to speak with a foreigner, asked this writer, “In the United States, are there paramilitaries? And what about guerrillas, do you have them too?”

Two soldiers patrol Tame's central plaza. Photo: Eric Fichtl

Despite the massive military and police presence and the efforts of the army to foment an atmosphere of co-dependent trust with the citizenry of the municipality in recent years, the security that tameños dream of seems as elusive as ever. Even if the special detachment of soldiers and extra police does eventually stabilize Tame, the model is impracticable for all of Colombia’s medium-sized and larger towns. Moreover, forcing the guerrillas into the countryside and allowing the paramilitaries to take over strategic towns may look good on a drawing board, but in practice, as Tame demonstrates, it has few positive results and brings the conflict no closer to closure. This is in large part because the move to stabilize via the gun fails to address the underlying socioeconomic problems at the root of the violence, a fact not lost on one local priest: “Until there is a certain level of social justice, especially on the part of the state being more open to the people that need it, we won’t achieve a peace process or dialogue. Because unfortunately here there are a lot of poor people, despite the fact that this is a rich community… A large part of the territory is in a few hands, and the conflict is specifically about working to achieve social justice.”29

In their own words, the people of Tame express their hopes and fears for the future. A young soldier from the Soldado de mi Pueblo program sighs, “Things have to change. We have to get to the day when at least my family and I can have some sodas on a Sunday with no worries.”30 Says a local school teacher, “I know it’s hard, but we can live better. I hope so, because I have my sons, and I don’t want them to live like this, like I live now.”31 Mayor Bernal offers his own sobering take on the state of affairs in Tame: “To me this is an absurd war, and the solution is not war and more war. I don’t see it that way. I don’t believe that will solve the problem. If one group kills another one, and causes the other one to kill in return… No, this is a case of enough already. I believe that when our grandchildren tell the story of what happened here, they will say, ‘they were such savage people, such killer people, such cowardly people, with little sense, with no respect for the lives of others.’ There’s no respect here.”

Notes

Links were functional at the time of original publication.

1. “Frustran atentado en Tame,” El Tiempo (Bogotá), June 7, 2003, P. 1-5.

2. Author’s interview with Mayor Jorge Bernal, Tame, Arauca, June 9, 2003. All subsequent quotations attributed to this individual are from the same interview.

3. Author’s interview with Mayor Jorge Bernal, Tame, Arauca, June 9, 2003.

4. Author’s interview with local Judge, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003. All subsequent quotations attributed to this individual are from the same interview.

5. Author’s interview with Lt. Col. José Antonio Lopéz, Colombian National Police, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003. All subsequent quotations attributed to this individual are from the same interview.

6. Figures cited in a number of interviews with local officials, including the Mayor, Police Commander, and Fiscal.

7. Author’s interview with Capt. Paredes, Colombian Army 18th Brigade, Navos Pardo Battalion, Tame, Arauca, June 10, 2003.

8. Author’s interview with local Catholic priest, Tame, Arauca, June 9, 2003.

9. Author’s interview with Luis Alberto Rodríguez Salamanca, Fiscal, Tame Arauca, June 12, 2003.

10. Author’s interview with Lt. Col. José Antonio Lopéz, Colombian National Police, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003.

11. Author’s interview with Capt. Paredes, Colombian Army 18th Brigade, Navos Pardo Battalion, Tame, Arauca, June 10, 2003. All subsequent quotations attributed to this individual are from the same interview.

12. Author’s interview with Soldier From My Town Giancarlo Martínez Villamizar, Colombian Army 18th Brigade, Navos Pardo Battalion, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003.

13. Author’s interview with Col. Cruz, Commander of Colombian Army’s 5th Mobile Brigade, stationed at Navos Pardo Battalion base, Tame, Arauca, June 11, 2003. All subsequent quotations attributed to this individual are from the same interview.

14. Author’s interview with Soldier From My Town Giancarlo Martínez Villamizar, Colombian Army 18th Brigade, Navos Pardo Battalion, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003.

15. Author’s interview with local resident (anonymous), Tame, Arauca, June 11, 2003.

16. “Colombia Violence Spills Over from Security Zone,” Jason Webb, Reuters, July 8, 2003.

17. Interview with Dario Tulibila, published by the National Indigenous Organization of Colombia, May 28, 2003. Available at: http://www.quechuanetwork.org/news_template.cfm?news_id=809&lang=e

18. “Denuncian violación de indígenas,” Felix Leonardo Quintero, El Tiempo (Bogotá), May 15, 2003.

19. A summary of Colonel Montoya Sánchez’s comments and the full text of the ONIC’s denunciation are available at: http://colombia.indymedia.org/news/2003/05/3633.php

20. “Welcome to Saravena,” Jason P. Howe, June 13, 2003. Available at: http://www.conflictpics.co.uk/Dispatches/index.htm

21. Author’s interview with Harvey D. Suarez Morales and Laura Zapata of the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (Consultoría de Derechos Humanos y el Desplazamiento, CODHES), Bogotá, June 13, 2003.

22. Author’s interview with Capt. Paredes, Colombian Army 18th Brigade, Navos Pardo Battalion, Tame, Arauca, June 10, 2003.

23. Figures cited in “Protecting the Pipeline: The U.S. Military Mission Expands,” Colombia Monitor, published by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), May 2003, p. 2. Available at: http://www.wola.org/Colombia/monitor_may03_oil.pdf

24. Uribe quotation in “Columbian PM [sic] Uribe Warns Leftist Rebels Can Only Run Away in ‘Spaceships’,” Agence France Presse, July 18, 2003.

25. Author’s interview with selected staff of the Hogar Juvenil Campesino, Tame, Arauca, June 11, 2003.

26. “Teachers Caught in Crossfire of Colombia’s Drug War,” Gary Marx, Chicago Tribune, August 3, 2003.

27. Author’s interview with local Catholic priest, Tame, Arauca, June 9, 2003.

28. Author’s interview with two teenagers (anonymous), Tame , Arauca, June 10, 2003.

29. Author’s interview with local Catholic priest, Tame, Arauca, June 9, 2003.

30. Author’s interview with Soldier From My Town Don Alberto Guantame, Colombian Army 18th Brigade, Navos Pardo Battalion, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003.

31. Author’s interview with local teacher, Tame, Arauca, June 12, 2003.

Eric Fichtl is associate editor of Colombia Journal. He traveled to Tame, Arauca, in June 2003.

This special report originally appeared in Colombia Journal, an online journal that was published by the Information Network of the Americas (INOTA).