Looking Back: Seventeen Years Since the El Mozote Massacre

Over 700 defenseless peasants were brutally murdered by a Salvadoran batallion that received U.S. military training and supplies.

This text originally published: 15 March 1999

Early in the morning of December 11, 1981, soldiers began rounding up the residents of a small village called El Mozote in the often rebel-controlled region of Morazán, El Salvador. The villagers were ordered out of their houses and into the tiny central square in front of the church. The men were separated from the women and children. For some time the population of the village, and others who had previously come from the surrounding towns having heard that El Mozote was a temporary safe haven from the ravages of war, stood in the plaza under the watchful eyes of the soldiers. In the distance, over the whining of the children, everyone could hear the sound of a helicopter approaching. As the aircraft touched down, the sex-segregated villagers were forcibly crammed into the buildings on the plaza, the women and children in houses and the men in the church.

What happened later that day was one of the worst human rights abuses ever to occur in a region unfortunately known for its human rights abuses. At El Mozote, in the space of a few hours, well over 700 defenseless peasants were brutally murdered by a special Salvadoran force called the Atlacatl battalion. Recipients of extensive U.S. military training and supplies, the Atlacatl battalion represented the Salvadoran military’s new approach to combatting the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) guerrillas who had proved themselves to be a force quite possibly capable of achieving a revolutionary victory within a few years’ time. The Atlacatl was to be the force that would crush the FMLN, cornering the guerrillas and simply annihilating them with superior firepower, strategy, and ability. With continued U.S. economic and military aid to the Salvadoran regime tied to the somewhat paradoxical dual ends of escalation of the war against the FMLN and the (at least symbolic) reduction of human rights infractions against the civilian population, the Atlacatl’s inability to engage the guerrillas in direct combat was incredibly unnerving.

Of course, the FMLN were not willing accomplices in the glorification of the Atlacatl battalion, and as the months passed and the guerrillas continued to evade the Atlacatl while successfully attacking other military installations, the men of the elite new force became increasingly frustrated. With the concept of a middle ground nothing more than a hindrance in wartime, the military mindset had become “if the campesinos are not with us, they are against us.” It was in this context that the Atlacatl battalion arrived in El Mozote, ostensibly seeking to interrogate the villagers about the guerrillas’ whereabouts.

The military helicopter landed bringing with it the officers of the Atlacatl. Soon the soldiers accompanied their leaders in a loud, gunpoint mass interrogation. The villagers, still hoarded in the buildings, were accused of collaboration with the FMLN, a dubious charge considering the known evangelical Protestantism of the community and their general rejection of the revolutionary pronouncements of the guerrillas. Some of the villagers were dragged out into the plaza, prodded along by bayonets attached to the ends of the soldiers’ American M-16s. Made to lie on the ground as shouting soldiers walked around them, or to stand blindfolded in crowded buildings with machine guns pointed at them, the villagers knew what was coming. The nearly 800 campesinos in El Mozote that morning were questioned for little more than an hour, and then, with the alleged information extracted, the Atlacatl troops set about making an example of the villagers for any other supposed collaborators in the surrounding countryside.

The Atlacatl battalion knew that a strong action at El Mozote could send a powerful message throughout the rebel stronghold of Morazán. In this war where all civilians were regarded as guerrilla sympathizers, the soldiers did not hesitate to make a curt and brutal statement of their intent to re-establish order at any cost. The men of the Atlacatl were merciless. Children were hacked to shreds with machetes, their heads collapsed by the butts of rifles. Babies were tossed into the air and caught on bayonets, or hung from trees, or their infant throats were slit and they were left to die. Girls in prepubescence and their slightly older sisters were dragged up into the hills surrounding the village and gang-raped before being shot, choked, or chopped up. The men were forced to the ground, condemned as collaborators, and shot in the backs of their heads; some soldiers emptied entire magazines into one or two hapless victims here or there. The women who were not raped were taken from the center of the village in small groups and executed. Their children, some of whom remained in detention in the houses, could do nothing but cry and mess themselves as their parents were systematically eliminated. When the majority had been killed, the Atlacatl soldiers set fire to the buildings. Some villagers were burned to death as they nursed their bullet and machete wounds. With the village alight and their work finished, the soldiers rested and drank. Their message had been sent.

What is known about the massacre at El Mozote comes from a variety of sources. A few villagers did survive. One, Rufina Amaya, a mother and wife who lost all of her family that December morning, managed to escape into the thick underbrush surrounding the village, where she laid listening to the horrors occurring just a short distance away. Her eyewitness account became a cornerstone for investigation into the massacre. The guerrillas came across the hundreds of bodies and the remains of the town and eventually Amaya, and they broadcast her testimony over their mobile Radio Venceremos, a move which quickly attracted national and international attention. The governments in San Salvador and Washington immediately dismissed the reports of the massacre as FMLN propaganda seeking to derail U.S. funding to El Salvador. Reporters from the two most respected daily newspapers in the U.S., the New York Times and the Washington Post, trekked overland from the Honduran-Salvadoran border with guerrilla guides to investigate the claims of a mass killing. Their reports made front-page headlines in the U.S. at a time when the Reagan administration was under intense pressure to cut off aid to the Salvadoran regime that had time and time again proved itself either incapable of limiting or unwilling to stop the excesses against the civilian population committed by the military in its counterinsurgency campaign against the FMLN.

Later, after the 1992 peace accords ended the war if not the inequities in El Salvador, a team of Argentine forensic anthropologists who had worked to uncover the secrets of their own military government’s dirty war arrived to excavate the site, identify the remains, and explain what had transpired. Many hundreds of victims could not be identified, as their bodies were maimed beyond recognition and their relatives were killed simultaneously with them.

The massacre at El Mozote, no matter how much the U.S. government sought to deny it, did occur. And it occurred in large part because the U.S. was desperately trying to avoid “another Nicaragua” in El Salvador. With direct U.S. intervention out of the question after the public outcry over Viet Nam just a few years earlier, the U.S. allied itself with one of the cruelest and most murderous militaries in the Americas. Moreover, three consecutive administrations—those of Carter, Reagan, and Bush—saw fit to grant El Salvador over $4 billion in U.S. funding in just over a decade of fighting. Whether it was stabilizing economic aid that allowed the feeble Salvadoran regime to carry on, or military aid that allowed the savage Salvadoran military establishment to repress ever more efficiently and to kill ever more easily, the effect of the U.S. aid was often brutal and helped to keep the tiny nation at war for longer than anyone expected. The bullets uncovered by the forensic team at the massacre site were stamped with U.S. military markings, the M-16s used were standard issue U.S. weapons, the helicopters used to transport the rapid reaction Atlacatl battalion were U.S. Hueys, and the members of that brigade had received their counterinsurgency training from the U.S. at the Southern Command School of the Americas in Panama.

In effect, the Atlacatl battalion was the centerpiece of the U.S. attempt to employ another army to fight its fears of a leftist (not necessarily Soviet-allied) state in its cordon of security, Latin America. Throughout the war the U.S. government would fabricate documents “proving” vast amounts of Soviet intervention and outlining fantastical tales of Sandinistas canoeing into El Salvador to fight alongside the FMLN. The U.S. would lie, delete or suppress information, deny the reports of its own press and occasionally its own Embassy officials, of witnesses, of refugees, and so on in a vain effort to justify its enormous effort to keep a malleable regime in El Salvador.

After years of denials and smokescreening and inhumane decisions to increase funding after unceasing flagrant human rights abuses, in 1991 the U.S. finally had to admit that the massacre at El Mozote had taken place and had been the work of the very military the U.S. had trained, funded, and indirectly directed. The U.S. Embassy in San Salvador dispatched two envoys to participate in a memorial ceremony at the site of the massacre.

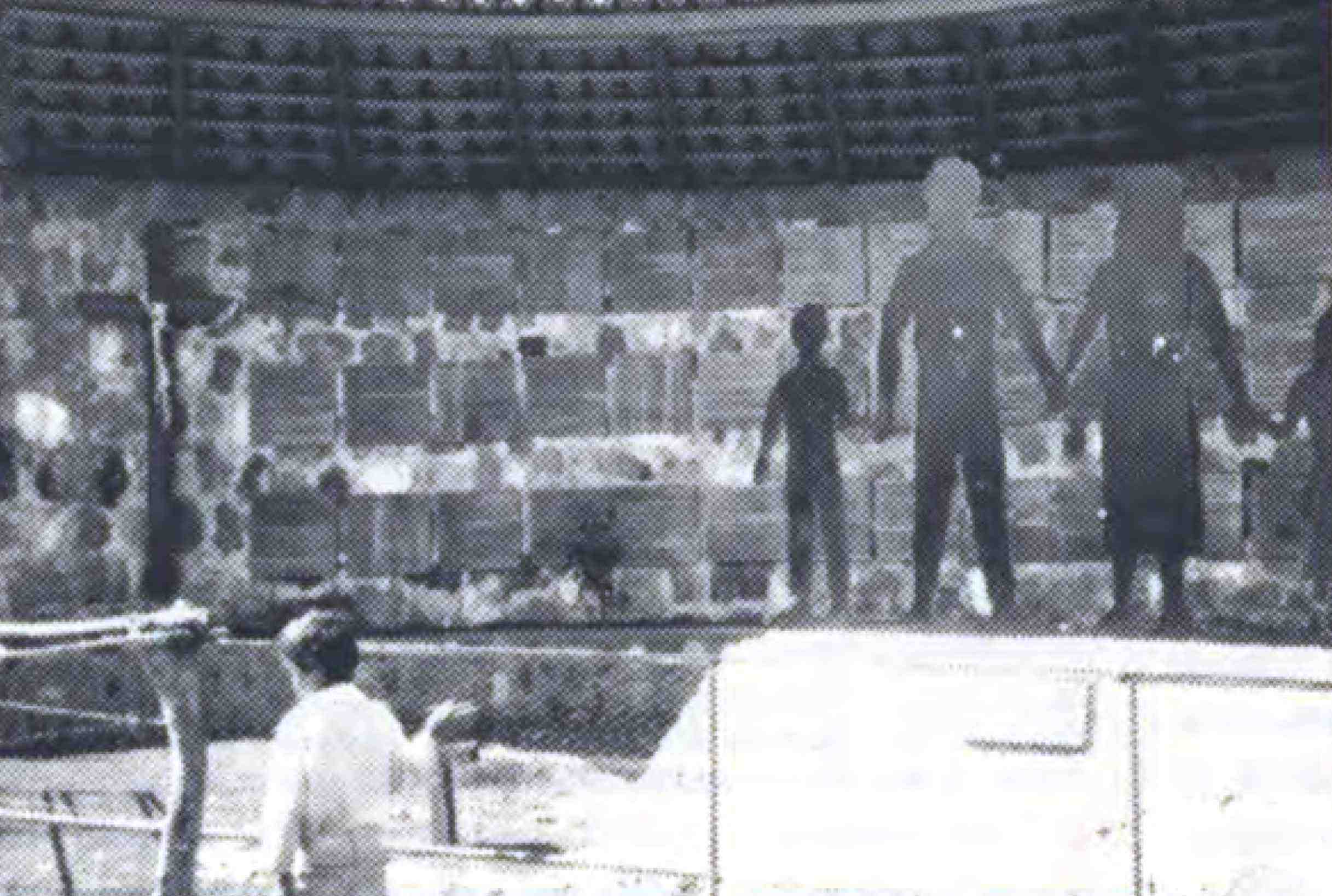

Seventeen years have passed since the massacre at El Mozote. I had the opportunity to visit the site of the massacre in March of 1997. It was an eerie discovery to find that campesinos have begun to resettle the area, some of them using the burned-out, bullet-ridden walls of the old houses in the construction of new ones. On the site of the church where the men were detained and where some were burned alive a new church is being erected. The plaza where the helicopter touched down, where hundreds were interrogated and lined up and led off from to be executed, is now the crossroads of a new, fledgling village. There is one tienda there, and the children of the new El Mozote gather to eat icicles under the shade of a tree, seemingly oblivious to the history of the place. The only reminder of what occurred there aside from the ruins of buildings is a simple memorial showing a silhouetted family of four holding each others’ hands. They are nondescript, sculpted from sheet metal, painted black. Behind them a wall bears the names or descriptions of those who were murdered.

Notes

For a more thorough investigation of the massacre and the subsequent U.S. denials, see Mark Danner’s The Massacre at El Mozote. Vintage, New York. 1994.

For a visceral vision of Salvadoran society at the moment just after the massacre, see Joan Didion’s Salvador. Washington Square Press, New York. 1983.

For a fictional account of the daily lives of Salvadoran peasants during the civil war, see Manlio Argueta’s One Day of Life. Vintage, New York. 1980

First published in La Quinta Raza Broad Sheet/Hoja Grande, Jan-Mar 1999

Download PDF (PDF contiene resumen en español también)